Few writers have been more misunderstood than Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. J. Hampden Jackson argues that a re-evaluation of Proudhon's work is in order, and that Proudhon's arguments against centralization make him a relevant figure to the present day. Published in politics, October 1945.

Nothing will seem more remarkable to future students of this decade than the heavy fatalism that has weighed over all political thinkers, from the philosopher and the statesman to the ordinary man ruminating over his newspaper. For one reason or another, we all seem to be accepting as inevitable the coming of increasingly totalitarian states, of new Leviathans. Totalitarianism on the Nazi model will, we believe, be destroyed, but in Germany as in the Catholic countries new presbyter may well be old priest writ large. Totalitarianism on the model of the Bolsheviki and Kuomintang will, we think, survive, and in the small nations there must be co-ordination and concentration of power. In the great democracies themselves the expectation is of increased State control, not only over finance, commerce and industry, but over education, health and leisure activities as well. No one seems to regard these tendencies with much enthusiasm, but everyone seems to think them inevitable. Many people are appalled by the prospect of the bureaucracy which must be entailed by bigger units, political, economic and social, but no one believes in an alternative. Somehow, we say, the civil liberties, the dignity of the individual, must be preserved in the new Leviathan, but how, we have no time to think. Perhaps, if the right people are in control, all will be well. Meanwhile there are more urgent matters on hand.

Liberalism, which might have been expected to give the world a lead in this matter, is on the defensive. Was it guilty of acquiescing in Privilege, in Unemployment? An uneasy conscience keeps its standards furled, or sends them out bearing a strange device (New Deal, Common Wealth) to join the Salvation Army procession towards State Socialism. Social Democracy, on the other hand, is nailed to its own mast. Its whole testament, from the gospels of Marx to the epistles of Lenin, insists on the extension of the power of the State. Not for nothing were the early Marxists called Authoritarians! not for nothing did the Webbs find their mecca in Moscow. All schools of Social Democracy from the Germans to the Fabians, have preached centralization. Now, according to their own inevitable logic of history, they are due to get it.

But is it inevitable? Is there no alternative to the totalitarian State under one guise or another? If socialists look back in the history of their own movement they will find one. They will find a tradition known variously as libertarianism, individualism, self-government, mutualism, federalism, syndicalism: a tradition usually described as Anarchism, which fought its first fight with Marxism nearly one hundred years ago, and its latest, but not its last, in 1936, behind the lines of Republican Spain. They will find that this Anarchist (no-ruler) tradition was stronger than that of Marx in the First International, which Marx disbanded—or removed to New York, it comes to the same thing—because so many of the delegates were Anarchists. They will find that their famous Paris Commune was the creation of men who called themselves mutualists or federalists and were no followers of Marx. They will find that the most radical section of the French working-class movement was composed of syndicalists who opposed socialism, both Marxist and parliamentary. They will find that the revolutionary workers who bore the heat and burden of the day in Switzerland, Italy, and Spain were Anarchists. And they may even find that the mass of the people of Russia in 1917 cast their vote against the Marxists and for the Social Revolutionaries who stood nearer to the Anarchist camp.

The father of this Anarchist tradition was Proudhon, who died in 1865, eighteen years before Marx. It was Proudhon’s disciple Bakunin who led the majority in the First International; Proudhon’s disciples—Beslay, Courbet and Gambier among them—who led the Paris Communards (the Manifesto of April 19th might have been drafted by Proudhon); Proudhon’s follower, Sorel, whose teaching was responsible for the charter of the French C.G.T. adopted at Amiens in 1906. It was a book of Proudhon’s that sowed the seeds of Anarchism in Catalonia and Andalusia, and Proudhon’s ideas, transplanted indirectly, that took root among the Social Revolutionaries in Russia.

It may well be that when our generation recovers from its fatalism and is disenchanted of its Etatism, Proudhon will come into his own as a prophet. The whole stress of his teaching was on Justice, which he defined as “ respect, spontaneously felt and reciprocally guaranteed, for human dignity, in whatever person and whatever circumstances it finds itself manifested and at the cost of whatever risk its defense may expose us to.” But this conception of Justice did not lead Proudhon into crude individualism. There is no dignity without liberty, no liberty without community, no community in a society of slaves, nor in a society divided into privileged and underprivileged, rulers and ruled. Society must be based on free association, of which marriage is the supreme institutional example. After the family comes the free union of co-operators, and after these mutualist units the federation. The movement must come from the bottom by contract, not from the top by decree. “I begin by Anarchy, the conclusion of my criticism of the idea of government, to end by federation as the necessary basis of European public law, and later on of the organization of all states. . . . No doubt we are far away from it, and it will take centuries to reach this ideal; but our Law is to advance in that direction.” The great enemy was the appetite for power, which reaches its apotheosis in the centralised state. Writing before either the German Empire or the Italian Kingdom was cemented, Proudhon insisted on the necessity of “conserving European equilibrium by diminishing the Great Powers and multiplying the small, organizing the latter in federations for defence.”

Few writers have been more vulgarly misunderstood than Proudhon. He is most generally known as the author of the slogan “ Property is Theft”; it is forgotten that he adds “Property is Liberty.” (The landowner’s rent is theft; the peasant’s proprietorship may mean liberty.) He is commonly believed to be a Utopian; it is forgotten that he was the most outspoken opponent of the Saint-Simonians, Fourierists and other French Utopians of his day. He is frequently held to have been a starry-eyed rhetorician; it is forgotten that he wrote of February 24, 1848: “The Revolution must be given a direction, and already I see it perishing in a flood of speeches”—and that he wrote this on February 25. He is thought of as a violent man; in fact, no more gentle creature ever used polemical language. He has been hailed alternatively as the Apostle of Counter Revolution and as the Prophet of the Barricades.

Most of the misunderstanding of Proudhon can be traced back to Marx (who was jealous of him) and to one more respectable cause. Proudhon was both the progenitor and the critic of Socialism. He was attacking not only the very present enemy, Capitalism, but also its probable successor, State Socialism. Hence the apparent contradictions in his work. He was criticizing both the present and the future. This is what makes his teaching so valuable to us in 1944; but it needs careful reading to disentangle the tenses. Not that he is a difficult writer. Critics have hailed him as one of the greatest masters of French prose. Sainte-Beuve, his first biographer, praised his style and called attention to his strict etymological use of words and to his debt to the great Latin authors and to the Bible. He wrote a vigorous and lapidary prose, and it is not so much his language that is difficult but the construction of his books which are confusing in their lack of balance and constantly changing angle of attack. He thought of himself as a metaphysician and sometimes as an economist, whereas he was a moralist first and last. That makes him easy for the unsophisticated to read and for the sophisticated to refute. (For English readers, his work awaits a translator; there is only one book available in our language.)

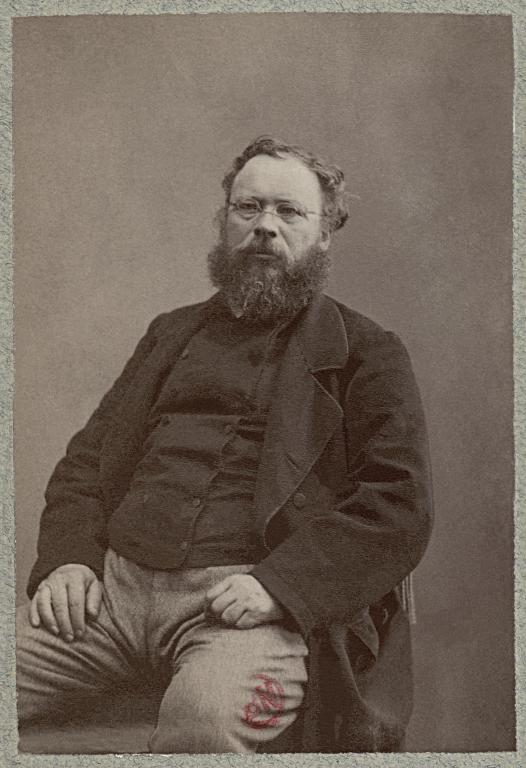

Moralists are often immoral men, as physicians are often invalids, and this is no valid criticism of their work. But how inspiring to find a man whose life bears out his teaching! Proudhon’s life ranks him among the rare saints of Socialism. He was born of working people, his father a brewery laborer in Besancon, his mother a servant doing heavy work in the brewery. Proudhon herded cattle on the foothills of the Jura for five years before being able, at the age of twelve, to go to school, where he was too poor to buy books and often had to go without cap or sabots. At nineteen he became a printer’s apprentice, and as a printer he made his tour de France. Most of his learning he picked up in the Besancon library and in the printer’s shop, where he mastered Hebrew and perfected his Latin while setting up an edition of the Bible. Circumstances made him a grammarian, and like Renan, he came to philosophy by way of philology, but the direction of his life’s work was clear to him from the beginning.

Submitting an essay for a prize at Besancon Academy, he addressed the examiners as follows: “Born and bred in the working-class and belonging to it now and always in heart, spirit, habits and, above all, in common interest and aspiration, the candidate’s greatest joy, if he were to secure your votes, would be . . . to be able in future to work unceasingly through philosophy and science with all the energy of his will and all the powers of his mind for the liberation of his brothers and companions.”

Proudhon won the prize—1,500 francs—and went to Paris to begin his life of self-dedication. As he had promised, he worked unceasingly, and as he had half expected, his work brought him poverty, prison, exile, debts and, most dangerous of all, notoriety. None of these trials broke him; indeed, the alchemy of his character turned each to spiritual gold. Poverty, though it sometimes drove him to accept fantastic employment as ghost-writer for a literary lawyer or as clerk to a canal-boat company, usually kept him near to the people whom he had made his cure. Prison—the easy-going imprisonment of the Second Empire—gave him leisure to write his best books and to take what he always held to be his wisest action, his marriage to the Parisian working-girl who was to tend him so lovingly for the rest of his days. Exile—in Belgium, from 1858 to 1862—was a harder cross to bear, as it is for all Frenchmen. On the surface of his mind his greatest worries were now about his debts. He was a continual but scrupulous borrower, one of the few who never lost a friend through owing him—or repaying him—money. His gift for friendship was equaled only by his gift for domestic life. Not all his tribulations, not even that of chronic ill-health brought on by overwork, prevented him from being a model husband and father. Indeed, this notorious revolutionary was a model of what have been called the bourgeois virtues. When he returned to Paris in the autumn of 1863 he was broken in health but intact in spirit. Perhaps he should be excused one senile lapse into optimism when, a few months after seeing his book, The Federative Principle,through the press and a few months before his death, he was approached by sixty working men who had issued a manifesto demanding representation in Parliament, he wrote, “La Revolution sociale marche bien plus vite qu'il ne semble.”

Such was the life of the man who was the champion of Self-Government against Etatism, or, as he would have put it, of Anarchy against Panarchy. Sooner or later there will be a reaction against the centralizing tendency which has characterized the political thought and action of our generation, particularly since the world economic crisis. The reaction may well be preluded by a revival of interest in Proudhon.