Is the working class movement dead?

The following article is loosely based on the notes for a pre-discussion talk by an AF member to a libertarian socialist discussion meeting in Leicester, 25 January 2017.

It is probably safe to say that over the last 30-40 years, there have been dramatic changes in what many socialists, communists or anarchists would recognise to be the working class movement. This is certainly the case in Great Britain, the main focus of this article, but similar changes have also taken place around the globe.

So, is the workers’ movement dead? In short: no, but it is on life support. Since the early 1980s there has been a marked decline in class consciousness, class cohesion and solidarity. Now, rather than being what can be termed a class for itself (that is, a working class in some way aware of itself of having markedly different interests and in opposition to the capitalist class), we have a working class that has become de-educated, de-politicised, atomised and individualised. Rather than seeing itself more-or-less in opposition to the ruling class, there is now a greater degree of perceived commonality with our oppressors and a passive acceptance of the status quo. This has gone hand-in-hand with an increase in nationalism, populism, rugged-individualism, popular entrepreneurialism, a vapid celebrity culture and the tendency to either wear one’s ignorance like a badge of honour or hold the view that we should rise above our class rather than rise with our class. In terms of class struggle politics, it is as if we are starting from scratch.

A bit of nostalgia

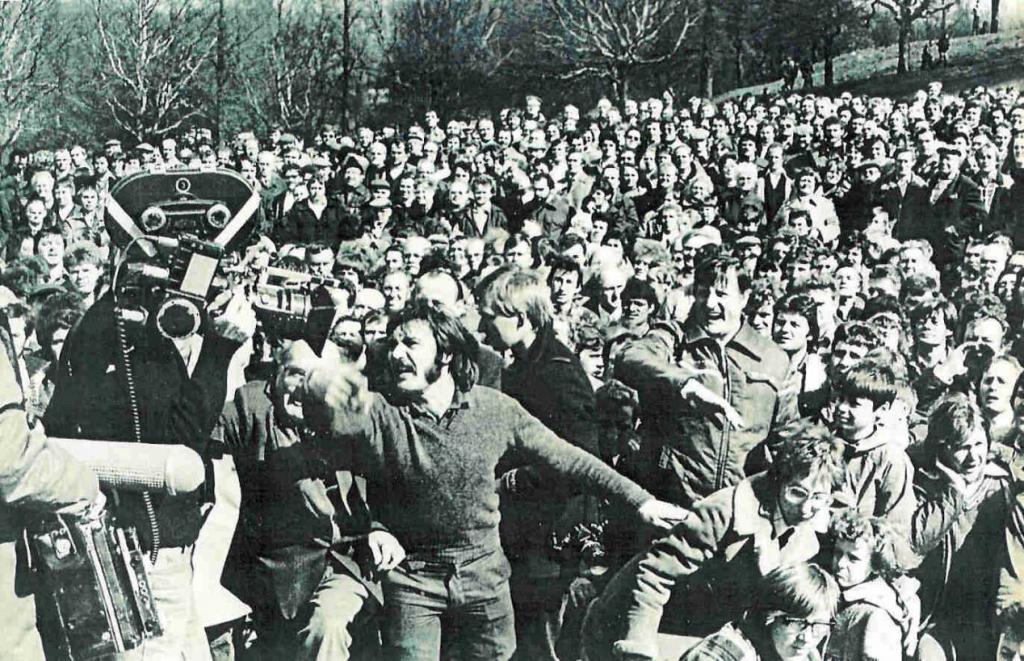

The 1970s was very much the post-war high point in terms of class struggle and the activities of the organised working class. The decade featured significant struggles from widespread wildcat miners’ strikes in 1969 to the “winter of discontent” of 1978-1979 in which there were mass strikes across the public sector, road haulage, the motor industry and others. The decade also saw miners’ strikes in 1972 (which included folkloric episodes such as the Battle of Saltley Gate) and 1974 (culminating in the fall of Edward Heath’s Conservative government after it had earlier imposed a three-day working week in order to conserve coal stocks) as well as countless strikes, both official and unofficial, taking place across many industries.

That such strike action was known on the continent as “the British disease” seems hard to believe when we look at the situation today. I recently received a document from a comrade in the Communist Workers’ Organisation which quoted from the UK Office of National Statistics (1) and noted that in 1979, 29.5 million working days were lost to strike action. You may wish to read that figure again as it’s a little hard to grasp. That’s 29.5 – almost thirty million days – lost because of strike action in 1979.

Fast forward closer to the present and the same Office of National Statistics gives the figures for 2015 as 170,000 strike days – a mere fraction but slightly better than I would have thought. But what that more recent figure doesn’t tell you is the quality of the action taken. I am assuming that the vast majority of the 170,000 strike days taken in 2015 were official actions, one day strikes and often token “days of action” that cause little inconvenience to management and have negligible effectiveness – unless the objective is to make us in some way feel morally right compared to our unscrupulous dastardly employers.

Contrast that with the wildcat nature of many strikes in 1979, actions that were often taken in spite of or against the trade union bureaucracies. With such actions, it was generally acknowledged that the objective was to cause maximum disruption to business as usual, and this is generally what we did. I would also suspect that a good number of industrial actions taken in 1979 were not necessarily listed in the official statistics. From my own experience, working at the time in a factory with low union density, where we all sat down on the job until our demands were met, it is doubtful that such an action would have appeared in any government statistics. Nor do I think we were alone in that kind of spontaneous action, as there really was something in the proletarian air that year.

Currently, we are a world apart from the level of class consciousness and solidarity that allowed such militant activity to take place. Yes, there are exceptions such as the struggles of the rail and London Underground workers, or the mass wildcat strikes by building workers a couple of years back. But by and large, what stands for a working class movement today in no way reflects working class reality and where anything resembling a “workers’ movement” does exist, has mostly retreated into crass reformism and identity politics – where we are defined by our differences and where more radical workers place their trust in the likes of Len McCluskey and Jeremy Corbyn; trust in a Labour left that seems comparatively radical compared to the Blairite-Thatcherite brand of neo-liberalism we’ve all been spoon-fed for years. Meanwhile, sites of genuine class resistance appear today as tiny oases in the vast capitalist desert.

That said, it’s possible I’m offering a somewhat rose-tinted view of the past. After all, while the 1970s saw inspiring acts of working class activity, it was also a period of chronic racism at all levels of society, where sexist attitudes were endemic and violent homophobia more or less the norm. Those were the days of The Black and White Minstrel Show, Miss World and Love Thy Neighbour on TV. A woman’s place was generally considered to be pretty much in the kitchen. Enoch Powell maintained a level of popularity, while the fascist National Front had an increasing presence. And back then, being part of what we now call the LGBT community was all you really needed to get yourself either roughed up by the cops or a good kicking from those who believed they had a licence to queer-bash. Thankfully, such reactionary views became increasingly unacceptable over the years – although, more recently, it looks as if there’s something of a backlash with racist, xenophobic and conservative attitudes apparently on the increase.

As for the mass industrial action and wider class consciousness of the 70s, yes it was often militant and often wildcat in nature, but it was also solidly tied to Labourism, or to a declining Communist Party which was being supplanted by the Trotskyist left. Whatever the position, it was all basically reformist, connected to the various strands of left capitalist politics and the orthodoxy of the trade union bureaucracies. Importantly, the 1979 high point of class struggle was quickly followed by a Thatcher government that was not simply elected by the rich but by swathes of the traditional working class. In response, there has been over the last 30-odd years the open collusion of the trade unions themselves with the collapse of their own movement – whether this was to protect funds from sequestration by the courts, to play it safe, not rock the boat and wait for an eventual Labour government (in those dark Thatcher days), or whether it was simply to not “go back to the 70s” when unions had lost control over their more militant membership. Either way, it’s now 2017 and we are in a culture where scabbing is no longer considered shameful, where younger workers often don’t know what a picket line is for and where UKIP is seen by many as more relevant than unions (2).

While I have looked at the changes that have taken place in the workers’ movement in Great Britain, as I mentioned earlier, workers in most other countries could probably relate a similar experience. But there are also occasional differences. For example there have been significant movements in East Asia, for example with textile workers in Bangladesh. There are also other expressions of resistance on-going in many countries – from time to time, including the UK. Nevertheless, we are a million miles away from a class conscious “class for itself” type movement, even in those areas of the globe where our class may be considered more “advanced” in terms of its revolutionary consciousness.

But the purpose of this article isn’t to take a walk down Memory Lane, it’s to look at and more fully appreciate where we are now as a class, and to think about what is possible and what we can do.

So if it’s all so dire, is it worth reviving?

Yes, because class struggle is what we experience every single day of our lives; what we as workers all have in common, whether we realise it or not. More than that, class struggle is the fundamental basis, the only way to ever abolish capitalism, should we as a class ever decide to do so. This is because, if we ever want to see a revolution, it will not be a revolution carried out by the well-meaning or the indignant of whatever class (though they would certainly have a role to play) but by those who have the actual power to shut down all industry and halt business as usual. Ultimately, capitalism can only be abolished by the workers of the world collectively taking control of the means of production, administration and distribution and establishing a society based on need not profit. And while such a scenario may seem highly unlikely in the here and now, we live in a world that is highly susceptible to change. What may seem impossible today may be the only realistic possibility tomorrow.

So what should be the role of pro-revolutionaries? All those years ago, the First International declared that the emancipation of the working class was the task of the workers themselves, and this still holds true today – however far away the notion of the working class emancipating itself may currently seem. Nevertheless, there are no short cuts to this goal. Well, no short cuts that won’t end in disaster in one way or another.

I say this because these desperate times make it feel as if we should be applying desperate measures. We shouldn’t. It’s not about us – and by us, I mean those who wish to see the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist system and the abolition of the state. It’s about the workers of the world doing exactly that. So that means we need to oppose substitutionism – in other words, substituting one’s particular group, party or political movement for the working class itself. This may appear to be basic common sense but we’ve seen the tendency to substitute in various left sects that see their own organisation or group as the be-all and end-all, the one sure road to revolution, the voice of the proletariat.

While Trotskyism, Maoism, Stalinism or any other Jacobin-derived Leninist variant should be given a wide berth for the obvious reasons, so-called insurrectionism (whether “anarcho-” or otherwise) is also best avoided. Granted, any potential revolution would be highly likely to include an insurrectionary element in the face of a ruling class which refuses to give up its power and privilege but instead unleashes increased repression. But the notion that a small and secretive group can encourage an alienated and generally de-politicised working class to action or can even help bring about the downfall of capitalism is a delusion of grandeur and reeks of cultish substitutionism. All of the above examples, in their own particular way, aim to act for, or in the name of, the working class rather than the working class acting for (and eventually emancipating) itself. They are all every bit as much a dead end as the hopeless reformism of those former anarchists who have recently opted to throw in their lot with Corbynism and the Momentum group.

The alternatives, however, may not be very exciting but they are essential. Those of us who advocate a revolution to establish a society based on the principle of from each according to ability to each according to need, whether we call ourselves anarchists, communists, socialists or whatever, need to maintain a level of revolutionary intransigence in the face of ever-prevalent reformism and opportunism. At the same time, we need to serve as a class memory that learns the lessons of our past, our mistakes, our triumphs and our inspiring moments. In other words, we need to be part of the “thin red line” that defends a solid revolutionary position.

But maintaining a revolutionary position is not enough. The best revolutionary ideas mean nothing if we are incapable of applying them to on-going struggles. So, we need to be practically engaged in struggles as and when they arise; involved, whether active within or supportive externally to those “oases” of class struggle I mentioned earlier. This also means being proactive in any attempts to organise autonomous workplace activity, organisations such as residents’ groups, claimants’ groups; and establishing or re-establishing such organisations but without repeating our past mistakes. And while I say this, I’m also aware that these days, such types of organisation are few and far between. I’m also aware that involvement in everyday activities (especially in these decidedly non-revolutionary times) can be easily channelled or co-opted in a reformist direction. It’s important that we recognise this danger and remain vigilant, participating as pro-revolutionaries and maintaining a level of revolutionary intransigence.

Finally, where we are active (whether actively participating within struggles or offering solidarity from outside) we need to engage with action that is meaningful. And when I say meaningful, I’m minded of the quote from the old group, Solidarity:Solidarity wrote:

Meaningful action, for revolutionaries, is whatever increases the confidence, the autonomy, the initiative, the participation, the solidarity, the equalitarian tendencies and the self-activity of the masses and whatever assists in their demystification. Sterile and harmful action is whatever reinforces the passivity of the masses, their apathy, their cynicism, their differentiation through hierarchy, their alienation, their reliance on others to do things for them and the degree to which they can therefore be manipulated by others - even by those allegedly acting on their behalf.

__________________________________________

(1) See also Smith, S.W. (2003), Labour Economics (2nd ed), London: Routledge, p206

(2) This should not in any way be taken as an endorsement of trade unionism by the author.