Highs and lows of a wage rise - the new garment minimum wage

(re-post)

The Bangladeshi minimum wage board has, after long negotiations, announced a 76% increase in garment workers’ pay, applicable to all seven pay grades. This has quickly been hailed as a great victory by some observers. We’ll go into the details to show that it’s not the result the workers continue to demand and that any gains may not be long-lasting.

The minimum wage increase being granted at this time is a result of particular circumstances. The past year has seen both the Tazreen fire and the Rana Plaza building collapse, bringing the combined deaths of over 1200 workers. These disasters increased pressure on international buyers, local garment bosses and the Bangladeshi government to begin substantial reforms in health, safety and pay to try to restore threatened global consumer confidence and distance the industry from the exploitative sweat shop image it had deservedly earned itself. EU and US buyers, labour organisations and states pressured with carrot and stick; promises of aid to upgrade infrastructure coupled with threats of withdrawing preferential trade tariffs. NGOs and trade unions intensified their campaigns against sweat shop conditions and influenced negative media coverage.

Bangladeshi suppliers have been concerned not to lose trade to rival Asian producing nations who could demonstrate better working conditions. The government wants to ensure the stability and growth of the industry central to its economy, which provides over 75% of its export earnings and around 15% of GDP. But the ruling Awami League party is also preparing for a general election in early 2014 and must try to win the votes of the mass of 4 million garment workers (comprised of 85% young women) and the support of the powerful industrial lobby of their bosses.

Within this historical context the pay leap is likely to be considered as (optimistically) a one-off concession by the industry to improve Corporate Image, consumer confidence and ensure stability and increased productivity. (As well as the election prospects of the Awami League.)* * *

Wage weighed against allowance

If we break down the component parts of the wage rise we see that the 76% figure is not quite what it might appear. We’ll also see why many thousands of workers have continued to strike and violently protest all through the negotiations and continue to do so against the deal. For them it is no desired “victory”.

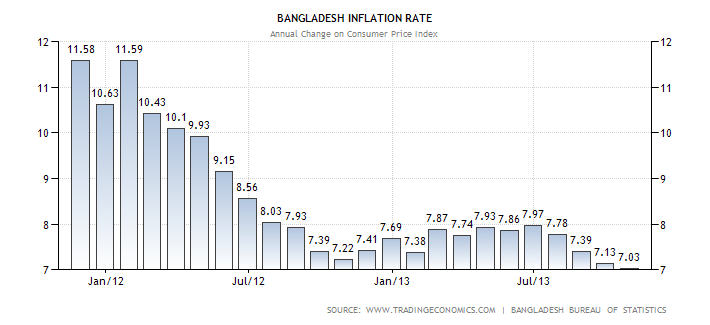

Firstly, the Taka 5,300 ($67) settlement for monthly pay is far below the Tk 8,114 ($103) generally demanded by workers, which is itself at the low end of what can be considered ‘a living wage’. Part of the wage settlement is a 5% yearly increase; but, as the graph below shows, inflation is running at 7-12% in recent months;

So the present settlement could be seen as an attempt to lock workers into an annual capped below-inflation rise – meaning a long-term decline in real income.

Worse, the Tk 5,300 total is composed of various parts; for entry level workers, Tk 3,000 would be basic pay, Tk 1,280 house rent, Tk 320 medical allowance, Tk 200 transport allowance and Tk 500 food subsidy. (Proportionately similar for higher grades.) As only Tk 3,000 is actual wage (rather than allowance) it will be this rate that will determine overtime rates rather than the TK 5,300 figure. This has been a source of dispute between bosses and unions during negotiations – and was made more so when the government overruled the wage board and conceded to the bosses that the basic pay component would be Tk 3,000 rather than the Tk 3,200 agreed during negotiations. Labour Minister Rajiuddin Ahmed Raju has already stated that

"the wage board has kept provisions of increment of salary as well, to be calculated on 5 per cent of the basic-pay of Tk 3,000." (The New Nation - 15 Nov 2013)[1]

So the basic pay component of Tk 3,000 can rise annually by 5% - but the Tk 2,300 allowance component of the overall Tk 5,300 wage appears intended by the bosses to remain frozen at its present level, its value soon eaten away by inflation. We can predict that next year there may well be conflict over the interpretation of this settlement.* * *

A struggle intensifying

In the two weeks since the wage deal was announced the main industrial hubs clustered around Dhaka - Ashulia, Gazipur and Savar - have become regular battlegrounds of massive crowds of workers in combat with police and paramilitary security forces. Three platoons of Border Guard (BGB) troops have also been sent into the industrial zones.

It is to the undoubted territorial street advantage of the workers that the industrial areas have developed in an uneven haphazard fashion, with little strategic thought given to overall security planning or containment of public disorder. The dense concentrations of hundreds of factories crammed with thousands of workers mean small disturbances can quickly escalate from one workplace into mass acts of solidarity and that larger protests can be sustained for long periods. This poses a basic problem for security forces and employers; normally the cops would simply seek to clear an area or lock it down to suppress public disorder. But this means continuing and prolonging the work stoppage - and the tight turnaround times demanded by foreign buyers mean that millions of dollars are lost for every day that an industrial area is shut down.

At present the unrest continues; this week on Monday (18th Nov) two garment workers were killed, apparently shot dead, in clashes with cops while dozens more were injured, some with bullet wounds. Workers have met police and paramilitary tear gas, bullets and batons with road blocks, riots, fires, bricks and attacks on factory property. There have been hundreds of factory closures and the workers are now reported to be demanding Tk 8,300 – an increase on their former demand of Tk 8,114.* * *

Unions

“Our expectation has been fulfilled. I now hope the workers will not engage in any further unrest,” said Sirajul Islam Rony, workers’ representative on the six-member wage board. [...]

“Seeing the owners will now be paying them more, I also hope that the workers will be considerate and enhance their productivity,” Rony added. (Daily Star – 15 Nov 2013)[2]

The wage negotiations have also been used to try to establish the legitimacy of trade unions as representatives of workers’ interests. With full rights for trade unionism recently granted as part of the reforms over fifty unions are now promoting themselves as self-appointed representatives of garment workers’ interests. Yet most of them are mere auxiliaries of small leftist parties with tiny memberships and little or no experience of functioning as workplace negotiators. Most union leaders are not and have never been garment workers themselves but are Party cadre and/or allied to NGOs as academics, lawyers etc. They see for themselves a role typical of middle class professionals; mediating in the interests of social peace and cohesion between the claims of workers, capitalists and state. They share the obsession with economic development and productivity of all those classes above the workers who seek to utilise workers’ labour power to build the nation state and economy. They seek only to moderate the inevitable class conflict involved in class exploitation and ‘humanise’, insofar as possible, the alienated labour of the wage slave. They seek to develop more modern and productive forms of alienation. The establishment of the legitimacy of their own mediating and representative roles are part of this modernisation.

But the unions and bosses have a struggle ahead to find acceptance for either a trade union ‘leadership’ that leads little except its own ambitions or the wage deal it has negotiated. For months, all through the negotiations, thousands of workers have self-organised wildcat strikes, demonstrations and riots to demand a wage of Tk 8,114. And these struggles are only a continuation of a garment workers’ culture of militant solidarity stretching back more than three decades.

“However well-intentioned, the function of those promoting union representation is to seek to repress the self-organising agency of workers and to reduce it to the legally enshrined 'right' to vote for and follow one or other of these specialists in representation. Unions will, if allowed, develop bureaucratic procedures that its atomised members must follow; deliberately fragmenting the present powerful unity of workers and their explosive spontaneity derived from both necessarily covert methods of organisation and from a shared culture of militancy.” (Previous article, “Who can ride the garment tiger?” - libcom Sep 2013)[3]

The ongoing agitation by workers most likely increased the wage settlement above what the garment bosses desired. Like the class struggle in the garment sector generally, that violent agitation has not been dependent on the presence of unions and they would have played at best a small part in its organisation, as they have freely admitted[4]. The union leaders have repeatedly urged workers to stop being violent, to follow their lead, go back to work, improve productivity and patiently wait for a (mediocre) deal to be struck on their behalf. So far, the workers aren’t playing ball and continue to show considerable powers of self-organisation. Long may that continue and advance...

NOTES

1] http://thenewnationbd.com/news-details/nn/2087/rmg-wheels-start-rolling-thenewnation

2] http://www.thedailystar.net/beta2/news/5pc-annual-hike-offers-long-term-solution/

3] http://libcom.org/news/who-can-ride-garment-tiger-01102013

4] As cited in, for example, the “Who can ride the garment tiger?” article.