The Story of Tea Workers

Philip Gain looks at the struggle of the labourers in the tea gardens

Conditions on the tea gardens were grim. In 1911 the Head of Government in Assam spoke out against a labour system that, "treated its workers like medieval serfs." Every few years new laws were drawn up in an attempt to impose minimum standards to protect the labourers on the plantations but these laws were largely ignored and unenforced, particularly as the local magistrates were planters. Companies used beatings, fines and imprisonment to keep their workers in line. Under British imperial laws trade unions were forbidden on the estates. Organisers who attempted to contact tea pickers were seen as trouble makers and accused of trespass. --British writer Dan Jones, 1986. "The tea gardens are managed like an extreme hierarchy: the managers live like gods, distant, unapproachable, and incomprehensible. Some even begin to believe that they are gods, that they can do exactly what they like." -- Francis Rolt, British journalist, 1991.

"Managers have anything up to a dozen labourers as their personal, domestic servants. They are made to tie the managers shoe laces to remind them that they are under managerial control and that they are bound to do whatever they are asked." --British writer Dan Jones, 1986.

Tea, the second most popular beverage in the world (the first is water), is believed to have first been popularised in China. For thousands of years the Chinese farmers had the monopoly of cultivating tea. Its cultivation in the tropical and subtropical areas is a recent phenomenon.

Tea plantation in India's Assam dates back to 1839. The first experimental tea garden in our parts was established in Chittagong in 1840 and the first commercial-scale tea garden in Bangladesh was established in 1854. Since then the tea industry has been through quite a few historical upheavals -- notable among them are the Partition of India in 1947 and the Independence War in 1971. Through these historical changes, the ownership of tea gardens established by the British companies on the abundantly available forest or government land has changed hands.

Right now Bangladesh has 163 tea gardens (including seven in Panchagarh where tea cultivation started only recently) with 36 of them considered "sick." One unique feature of the tea industry is that the entire land mass (115,000 ha excluding Panchagarh) granted for production of tea is government land. It is also for the colonial legacy that our tea gardens are huge in size and the management administer the gardens with the air of British Shahib and Zamindars. The use of grant areas for tea with 45% actually used for production of tea is another key concern. Land granted for tea cultivation but used for other commercial purposes is deemed unjust and an incentive for social injustice perpetrated on the tea plantation

PHILIP GAIN

workers.

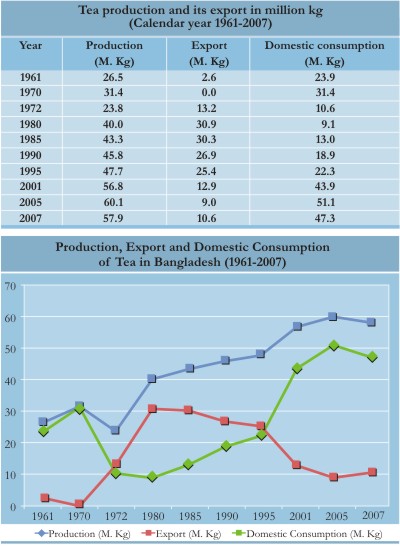

The most striking fact about tea production in Bangladesh is that after the partition of India most of the tea produced here used to be consumed by West Pakistan. After Independence, Pakistan remains to be the largest importer of Bangladeshi tea. However, now it is we who consume most of the tea that we produce. In 2007 Bangladesh produced 57.9 million kgs of tea of which only 10.6 million kgs were exported [82% of which was taken by Pakistan]. There is an apprehension that if the production of tea does not increase significantly and if domestic consumption continues to grow fast, Bangladesh will soon become an importer of tea. The bottom line is tea is no more an important export commodity and Bangladesh plays no significant role in the global tea trade although it ranked 10th among the tea-producing countries in 2007.

In the discussion on tea, its production, consumption and trade those who remain least attended are the tea plantation workers. The tea industry is very different from other industries. The production process of tea involves agriculture and industry. What is unique about labour distribution in these two areas is that the maximum of the labour force is engaged in agriculture -- the tea gardens or the field. The labour force that keeps the tea industry alive is not local. The British companies brought them from Bihar, Madras, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and other places in India to work in the tea gardens in the Sylhet region. The misfortune of these indentured laborers started with their journey to the tea gardens. According to one account, in the early years, a third of the tea plantation workers died during their long journey to the tea gardens and due to the tough work and living condition. Upon arrival to the tea gardens these laborers got a new identity, coolie and were turned into property of the tea companies. These coolies belonging to many ethnic identities cleared jungles, planted and tended tea seedlings and saplings, planted shade trees, and built luxurious bungalows for tea planters. But they had their destiny tied to their huts in the "labour lines" that they built themselves.

When they came first, they got into four-year contracts with the companies. That was the beginning of their servitude. More than a century and half or four generations have passed since the tea plantation workers settled in the labour lines. Their lives and livelihoods remain tied to the labour lines ever since. They are people without choice and entitlement to property. In addition to the wages, which is miserably low, they get some fringe benefits. The houses in the labour lines are given by the employer that comes first on the list of fringe benefits. One worker gets one house that is supposed to be maintained by the employer. However, generally the workers themselves do the repair and maintenance. Living conditions in houses in the labour lines are generally unsatisfactory and outrageous in many instances. Typically a single room [in the line house] is crowded with people of different ages of a family. Cattle and human beings are often seen living together in the same house or room. Some families try to construct an extra house or room for which they have to take permission from the management.

The wages -- daily or monthly -- is the single most concern. The maximum daily cash pay for the daily rated worker in 2008 was Taka 32.50 (less than half a US$). This is a miserable pay having a severe effect on the daily lives of the tea workers. Although the workers get rations at a concession, a family can hardly have decent food items on their plate. They indeed have very poor quality and protein-deficient meals. Their physical appearance tells of their malnourishment. Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU) that represents the workers and Bangladesh Tea Association (BTA) that represents the employers sign a memorandum of agreement every two years to fix the wages. The last memorandum of agreement went into effect on 1 September 2005. The two-year period of effectiveness of the agreement ended on 31 August 2007 [during the state of emergency in the country]. It was due to the state of emergency and squabbles between rival groups in Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union that no agreement between the two parties was signed in due time. However, in the absence of any agreement, the owners increased wages by Taka 2.5 as an interim arrangement. What is important to note here is that BCSU in its charter of demands placed to the owners have demanded increase of wages by up to 100%, but the owners increased it by Taka 2 every two years, which the BCSU accepted in the end. The newly elected leadership (in 2008) of the BCSU, in its charter of demands of 2009, demanded that the cash pay of the daily rated workers be increased to Tk.90.00 from Tk.32.50. It is yet to be seen how the employers respond to the demands of BCSU.

Fringe benefits other than houses include some allowances, attendance incentive, rations, access to khet land for production of crop (those accessing such land have their rations slashed), medical care, provident fund, pension, etc. BTA calculates the cumulative total daily wage of a worker at Tk.73. The newly elected leaders in BCSU have a different calculation, which is lower than that of BTA.

For a long time, The Tea Plantations Labour Ordinance, 1962 and The Tea Plantation Labour Rules, 1977 defined the welfare measures of the tea plantation workers among other things. In 2006 these laws along with other labour related laws (25 in total) were annulled and a new labour law, Bangladesh Labour Act 2006, was introduced. The tea plantation workers were brought under this Act. The new Act has fixed the minimum wages of industrial workers at Tk. 1,500 (US$22). The tea plantation workers, who got lower wages in cash than this minimum wages, raised their voices for an increased cash pay. They were turned down. In a letter dated 20 July 2008 the Deputy Director of Labour, Tea-industry Labour Welfare Department in Srimangal, Maulvibazar announced, "the minimum wages announced in the gazette was not for the workers in the tea gardens." The letter also mentioned that "the government has already formed a separate wage board to determine the wages for the tea workers and the issue of minimum wages is under consideration." It is yet to be seen how the wage board makes progress in its work.

If compared with wages of the Indian tea workers, the wages of Bangladeshi tea plantation workers is much lower. In Darjeeling, Terai and Doars of West Bengal in India the daily wages of a tea plantation worker was Rs.53.90 in 2008. The wages, increased in three steps, will reportedly become Rs.67 in 2011. Strong labor movements have been instrumental in such wage increase. In West Bengal about 400,000 workers will get this increased wages. Compared to the Bangladeshi tea plantation workers, the Indian workers also get a better deal in accessing fringe benefits such as rations, medical care, housing, education, provident fund benefits, bonus, and gratuity. What puzzles one is that the auction of prices of tea in Bangladesh is high compared to the international auction prices while its production cost is comparatively lower than other tea producing countries (India, Sri Lanka and Kenya for example). Of course the productivity of tea per unit in Bangladesh is lower compared to those countries. Many believe that there is no justification for low wages of the tea plantation workers in Bangladesh. They deserve much higher wages.

The work condition of the tea workers who spend most of their working time under the scorching sun or getting soaked in rains is a concern. A woman tealeaf picker spends almost all her working hours for 30 to 35 years standing before she retires. The working hours for the tealeaf pickers, mostly women, are usually from 8 AM to 5 PM [7-8 hours excluding break for lunch] from Monday to Saturday. Sunday is the weekly holiday. To earn some extra cash, the extra work brings additional grief.

PHILIP GAIN

Education, an important ladder for transformation of a community or society for betterment is at the root of the social exclusion of the tea workers. There are schools in the tea gardens. According to the Bangladesh Tea Board (2004), in 156 tea gardens (excluding those in Panchagarh) there were 188 primary schools with 366 teachers and 25,966 students. Given that the employers provide education, the government schools in the tea gardens are just a few. In the recent times, the NGOs run significant number of primary schools. The quality of education provided in these schools remains to be a concern. An overwhelming majority of the children of the tea plantation workers drop out from school before they can use education to step into other professions and thus they have to enter the tea gardens as laborers.

The tea communities are one of the most vulnerable people of Bangladesh. They deserve special attention of the State, not just equal treatment. But unfortunately they continue to remain socially excluded, low-paid, overwhel-mingly illiterate, deprived and disconnected. They have also lost their original languages in most part, culture, history, education, knowledge and unity. In the labour lines of a tea estate, they seem to be living in islands -- isolated from the majority Bangali community who sometimes treat them as untouchables. Without fertilisation of minds, they have lost dignity in their lives. These are perfect conditions for the profiteers from the tea industry to continue exploitation of the tea workers. Deprived, exploited and alienated, the majority of the tea workers live an inhuman life.

The key questions to ponder: How longer will the tea communities stay confined to the labour lines? Will they continue to live as people without choice and entitlement to a land they have tilled for four generations? The employers probably want the status quo maintained for a steady supply of cheap labourers. But the tea communities, little more conscious now than before, want justice done to them. They want strategic services from the State and NGOs in the areas of education, nutrition and health, food security, water and sanitation, etc. They also want to see their languages, culture, and social identity protected.

PHILIP GAIN

Fearful of their future in an unknown country outside the tea gardens, the tea communities keep their voices down and stay content with meager amenities of life. As citizens of Bangladesh they are free to live anywhere in the country. But the reality is that many of the members of the tea communities have never stepped out of the tea gardens. An invisible chain keeps them tied to the tea gardens. Social and economic exclusion, dispossession and the treatment they get from their management and Bangali neighbours have rendered them to become captive labourers.

The government is showing the country a dream of a digital Bangladesh and changes in the lives of poor, marginal and Adivasi people. The tea plantation workers are not just poor, they are a particularly deprived marginal community in captive situation. They have limited scope to integrate with the people of the majority community and they face great difficulties in exploring livelihood options outside the tea gardens. The tea plantation workers want the State to address to address their case with care and translate its commitment to them providing political and human protection.

Philip Gain is the Director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD).