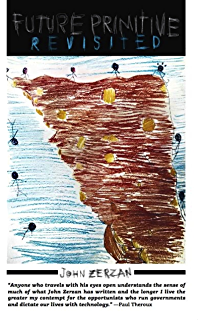

Commentry : Running on Emptiness by John Zerzan (Feral House, 2002)

(bangladesh asf)

John Zerzan has been one of the more popular anarchist writers of the past two decades. He is considered one of the main theorists of anarcho-primitivism or green anarchism. His neo-Luddite politics have come to be associated with the 1999 WTO protests a.k.a. “the battle of seattle,” “radical” environmentalism, and the unabomber. Running on Emptiness (Feral House, 2002) is an anthology of essays and interviews by Zerzan. The essays and interviews cover a diverse range of topics, from the origin of culture and oppression to abstract expressionism to Star Trek.

Zerzan’s revolution

According to Zerzan, for most of its pre-history, humanity existed in a golden age free from oppression. (68) Then, humanity’s original sin, symbolic thought or “culture,” enters the picture. Humanity’s battle with culture began sometime in prehistory, the earliest cave art is dated from roughly 30,000 years ago. (5) Around 10,000 years ago, “culture triumphed with domestication [of crops and animals].” (5,15) From there, humanity’s fall from Eden snowballed into society as a full-blown technological hell. And, just on the horizon, even greater nightmares await us with the further loss of humanity to the machine through robotics and cyborg technologies. “Progress has meant the looming specter of the complete dehumanization of the individual and the catastrophe of ecological collapse.” (79) The solution is to return to the ways of the past. So says Zerzan.

Many of the ideas in Running on Emptiness are drawn from Frankfurt School authors, especially the analysis of alienation, time, art, culture, etc. However, Zerzan also draws on a wide variety of other sources from philosophy, anthropology, linguistics, literary criticism, etc. Zerzan often makes wild claims with cherry-picked, little, or no evidence. For example, Zerzan causally mentions supposed super powers that humankind has lost in the modern world: super health, super vision, super hearing, and telepathy. Zerzan’s revolution would probably be objectionable even to many of his fellow anarchists. Zerzan longs for a world without literacy (10), without language and “verbal communication [which] is part of the movement away from face-to-face social reality” (10), without art, “there would be no need of art in a disalienated world” (11), without time (17-41, 75), without agriculture or technology. Zerzan quotes approvingly of James Shreeve who fantasizes about the Neanderthal’s supposed harmonious relationship with the world:

“… where the modern’s gods might inhabit the land, the buffalo or the blade of grass, the Neanderthal’s spirit was the animal or the grass blade, the thing and its soul perceived as a single vital force, with no need to distinguish them with separate names. Similarly, the absence of artistic expression does not preclude the apprehension of what is artful about the world. Neanderthals did not paint their caves with the images of animals. But perhaps they had no need to distill life into representations, because its essences were already revealed to their senses. The sight of a running herd was enough to inspire a surging sense of beauty. They had no drums or bone flutes, but they could listen to the booming rhythms of the wind, the earth, and each other’s heart beats, and be transported.” (2-3)

Zerzan’s First Worldism

Although Zerzan does recognize that some humans benefit from oppressing others, he draws the line between oppressor and oppressed incorrectly. Zerzan writes, “Just as Freud predicted that the fullness of civilization would mean universal neurotic unhappiness, anti-civilization currents are growing in response to the psychic immiseration that envelops us.” (1) In this Mercusean-type argument, everyone is an oppressed cog in the system, opening up the possibility of universal, human revolution; the system has dehumanized us all, therefore a radical, humanist revolution is possible. Implicit, although not always clearly stated in Zerzan’s book, is the claim that everyone or virtually everyone has an interest in destroying and radically re-making contemporary society. Such a belief is far off the mark. In reality, most First Worlders benefit from the way things are and have little interest in returning to Zerzan’s imagined Neanderthal-like way of life. Most Third Worlders do have an interest in changing the status quo, but not in the way that anarcho-primitivists like Zerzan imagine. The history of revolution of the past century has disproven First Worldism and confirmed Lenin’s prediction that the East, or more broadly, the Third World, has become the center of gravity of the world revolution. Against Zerzan’s First Worldist orientation, there are many examples where social revolution has been unleashed as part of Third World, national liberation struggles: China, Vietnam, Albania, Korea, etc. There are no significant First World, social revolutions. Thus confirming Leading Light Communism.

This First Worldism of anarcho-primitivism is also reflected in its view of imperialism and national liberation. Imperialism is barely mentioned in Zerzan’s work. In Zerzan’s criticism of “anarchist” Noam Chomsky, Zerzan expresses disdain for Chomsky’s focus on imperialism in Chomsky’s political works. (140-141) Theresa Kintz, author of the introduction to Running on Emptiness, explains the anarcho-primitivist view of imperialist wars against the Third World:

“Interestingly, heads of states are referring to what is going on as a ‘clash of civilizations’ — how true, for a change. The regimes currently challenging the West’s supremacy are authoritarian entities no less civilized than capitalist America.. It’s been going on like this for thousands of years. Even a cursory overview of history shows that as long as civilizations have existed they’ve made war on each other –always have, always will.” (xii)

The anarcho-primitivist view equates Third World national resistance with Amerikan aggression. For anarcho-primitivists, Palestinian resistance is equated with Israeli occupation. Just like other First Worldist utopians, anarcho-primitivists see imperialism and forces of national liberation as two sides of the same coin.

It is no surprise that Zerzan’s work says little of interest to Third World peoples who are the main force for social revolution in our epoch. Solutions to problems of poverty in the Third World such as land reform and development are absent from his work. Zerzan preaches the rejection of science and technology. Technology itself is evil in the anarcho-primitivist view. Yet peoples of the Third World are very aware that science and technology are necessary for liberation and development. Such naïveté is itself typical of First World utopians.

On post-modernism

Running throughout Zerzan’s essays is a critique of post-modernism as an intellectual sham that serves the system. Zerzan writes:

“PM abandons the ‘arrogance’ of trying to figure out the origins, logic, causality, or structure of the world we live in. Instead, postmodernists focus on surfaces, fragments, margins. Reality is too shifting, complex, indeterminate to decipher or judge… Meaning and value are old fashioned illusions, and so is the practice of writing with clarity.” (165-166)

Of the anarchist Hakim Bey, Zerzan writes:

“Bey’s method is as appalling a his claims to truthfulness, and essentially conforms to textbook postmodernism. Aestheticism plus knownothingness is the PM formula; cynical as to the possibility of meaning, allergic to analysis, hooked on trendy word-play.. A point of view that tries to be consistent, well-researched tentative exploration is deemed [by Bey]] absolutist, rigid, aggressive, the product of a ‘presumptive vanguard of the pure.’” (145)

Zerzan’s critique of post-modernism is for the most part correct. However, it is not clear how Zerzan sustains such a critique since it isn’t clear that he accepts science. Marxism, by contrast, rejects post-modernism and embraces science.

Real environmentalism

Zerzan’s worries about ecological catastrophe are justified.

“A hyper-technologicalized capitalism is steadily effacing the living texture of existence, as the world’s biggest die-off in 50 million years proceeds apace: 50,000 plant and animal species disappear each year.” (120)

However, Zerzan’s anarcho-primitivist solution in Running On Emptiness is a fantasy land. Rather, Leading Light Communists are the real environmentalists. It is only by resolving the principal contradiction between imperialism and the exploited nations in our favor that we can move to resolve other contradictions. The struggle against imperialism by the exploited nations is the only struggle that can unleash the social energy to make social revolution and environmental revolution possible. The anti-imperialist struggle is the key that unlocks other struggles. This has been shown over and over again in the last half-century of revolution. However, successful social revolutionaries like the Bolsheviks or the Maoists are lumped together with fascists by Zerzan. (86) Thus, Zerzan, like the failed anarchist tradition itself, fantasizes about a non-existent anarchist revolution while rejecting real resistance in the Third World and criticizing the workers and peasants who actually seized power and carried out socialist construction. One wonders why Zerzan takes pot shots at the Bolsheviks while embracing twentieth century anarchism. Surely Zerzan would have equally rejected the social revolution carried out by anarchists in the Spanish civil war or Russian revolution had such ever materialized. After all, the vision of social revolution of the anarchists of Spain or Russia surely had more in common with that of the Bolsheviks than with Zerzan’s Neanderthal utopia. The sense of this collection of essays is that anything short of rejecting civilization itself does not count. Zerzan’s work suffers, albeit to the most extreme degree, from the same problems that the anarchist tradition has always faced: lack of science, utopianism, no track record of achieving human liberation on any significant scale, etc.